Transdisciplinary analysis

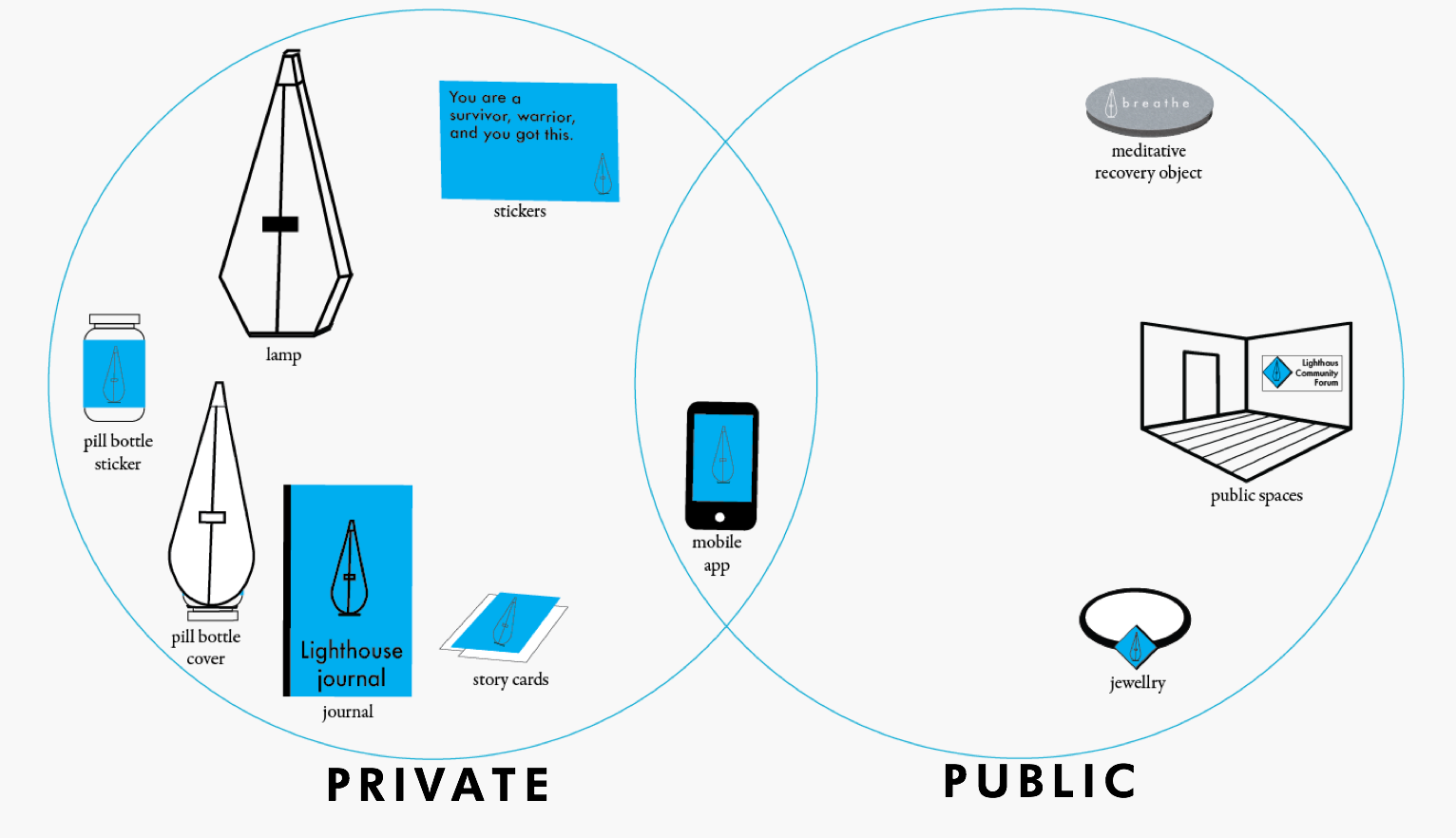

This work serves as an illustration of transdisicplinarity in practice which spans design, healthcare and politics, but also serves as a case study on how designers can remain open to how our work evolves during one project. I had originally set out with the concept of an intervention inspired by peers informally helping other peers in settings such as support groups, but found the transient nature of that structure as somewhat limited. The factors that keep a peer support group a successful model such as anonymity, and flexibility on commitment to formal membership structures also serves as an opportunity to build upon and explore how to create deeper bonds and what kind of system would be necessary to operationalize that new kind of ‘peer support group’. This finding – that we can design for openness, of systems that grow and evolve via peers participating and new mediums – is liberating and points to a different kind of civic engagement. The process out of the research phase led me to focus on objects as the main area of investigation for prototypes because they act as an interface connecting people and services, and became a way to explore transferring peer support into a more material form, something that could be used in a mobile, transient society. In this focus I came to see a new kind of literacy around ‘object literacy’ as part of recovery. The evolution of this work came to not only to consider the service around the creation of objects, but to see creating a ‘living service’[1] that evolves with the needs of communities. It moves away from viewing the treatment of illness as ‘one size fits all, one solution for a condition’ and more towards meaningful and customized solutions or multiple possible touchpoints that need not all be used, but are available for use. And when we speak of usage, the finding around interventions originally designed for private use that may ‘slip’ into public usage is a way to potentially change the conversation around self-stigma as those who experience mental illness may not feel the need to hide their illnesses through the use of these objects in public.

The slippage between evocative objects used in private now being increasingly used in public as a way to change the dialogue about mental illness, support objects and visibility and presence of illness.

All parts of how we structure our world as so often in flux in a time of rapid acceleration and uncertainty – from the organizations we depend on, to the products and services and experiences they create and how they are delivered, to the design methods we use in response to challenges and the technology which shapes the way those experiences evolve with time.

Design is uniquely positioned to tackle stigma and self-stigma because it is a shapeshifter – adaptable and multimodal, which can assume multiple roles across the spectrum of experience. It can act as an instigator (to ask questions), soothsayer (predicting the future) analyst (picking up on trends, connecting, making meaning), solution creator (creating products and services to solve), tool maker (creating products and services for others to use) – and uniter. It can translate and harness culture as driving force and create new cultures – but not just culture as artistic expression, but to translate culture into action, by creating cultural infrastructures. The benefit of a transdisciplinary design mindset in this work is to understand the systems and the people within them, never losing sight of the challenges at any scale but to recognize the possibility for design to evolve to better address our myriad of challenges, and the imperative for design to do so. By working at both the system and personal levels, zooming in and out, we not only envision new worlds but the multilevel infrastructures required to build and sustain these worlds. It seeks to create infrastructures to challenge existing systems to address gaps, leverage opportunities and make visible a meta-analysis of situations – the actors, operations, theory and motivations inherent in the creation of such systems.

Transdisciplinary design is by its very nature a mode that span, transcends, moves beyond, an approach that sees past paradigms that has plagued most design disciplines to rethink and remakes fundamental aspects of social structures – the heart of where stigma lies, and why it is vital in this space.

Conversations

The conversations I’m joining in this work is with those in recovery oriented medicine and peer support services, contributing design expertise and help explore how to scale them up and what level of authority is required to ‘run’ them. There are also conversations around new kinds of cultural infrastructures. On some level the work being done around urban design and mental health is something that could connect to my work; I see my work as an attempt to integrate more personalization and intimacy that can be lost when we move up to a more urban scale. I see a wider set of stakeholders interested in transdisciplinary design who many not be aware designers are interested in this space. Healthcare institutions, policy makers and advocacy groups could be participants to pilot out the work here, as are product design firms or artists interest in the creation of evocative objects. Design has an opportunity to work with those with a lived experience, and I could discuss my work with audiences of peer to peer support services and organizations/venues speaking of the benefits of using transdisciplinary design to integrate the human (and humane) more into our systems. For designers curious but hesitant to approach domains like healthcare because of the domain knowledge required or burden of proof, this work serves as a way to demonstrate how design contributes to exploring new kinds of services, methodologies and communities, – so there would be a benefit in connecting with them as well.

Contributions

This thesis work contributes by creating a methodology to understand mental illness and advocating for a transdisciplinary methodology. The concept of embedding self-reflexivity among consumers to better understand their relationship to illness is one of the unique aspects – it would be of clear benefit to self-stigma related work, but on a larger level an examination of our perceptions of illness, stigma and recovery may benefit all of us, and why illness is so often seen as a ‘individual’ issue rather than an opportunity to use collective support. We all will experience illness, perhaps misunderstanding and fear about the experience of illness and its treatment; the work of design here is to contribute to not only responding to challenges like self-stigma but to legitimize design as an exploratory tool to better understand illness itself. Perhaps it also will contribute to the dialogues about healthcare – not only how best to run it but how our values as a collective society need to demonstrate a commitment to all people to have access to healthcare as an issue of fundamental human rights.

[1] The Era Of Living Services. 1st ed. Fjord, 2017. Web. 9 Apr. 2017.

Impact

These prototypes and the idea of a new methodology of care point to a new kind of approach to combat stigma and create empowerment and community. More than a simply proposing a solution, this project asks service design to move towards possibly uncomfortable areas of culture, to embrace the ability of design to change culture and to see such work as valuable and essential for us as design practitioners. It seeks to explore creating new interventions that challenge stigma and create new possibilities of hope for the future that celebrate creating new self-authored stories about mental illness.

Conclusions

Projects that sit at the intersection of design, healthcare, policies and systems illustrate a need to be open to evolving how we create and collaborate across disciplines to untangle and unpack the messy implications of these complex terrains. It’s up to us to evolve how we design to make them as living, open, mutable as possible and acknowledge and live with their messiness. We will see there is no perfect final offering, and instead push our mediums, seek out new ways to evolve and see this as an ethical responsibility. This willingness to evolve our craft abandons the allure of closed final offerings – to embrace an openness that acknowledges the grays and questions in our work. To design peer to peer systems of care involves living in a ‘trans’ spaces beyond certainty of our roles as designers, consumers, medical professionals and others. To open our work up to participation could be seen as a loss of control, but the end of Genius Designers as Auteurs is an opening – a rupture – towards new ways of thinking and making. Alain Badiou reminds us “when all is said and done, all resistance is a rupture in thought, through the declaration of what the situation is, and the foundation of a practical possibility opened up through this declaration.” To understand the future of systems of care requires bravery in exploring; creating transdisciplinary artifacts and experiences is a way for for us to be open to multiple futures – both positive and negative. To be open to living systems may be intimidating, but also a source of liberation. These can be opportunities that empower us as creators to design works that explore the murkiness of ethics, the complexity of systems, and the uncertainty of future worlds. This openness can navigate us forward and provide hope in uncertain futures. This can mean more than just ‘finding forms to accommodate the mess,’ but also perhaps creating ways to thrive in the chaos, the unknown and the great dark wonders that lie ahead of us.

More than just Mental Illness – what does this speak to about all of us?

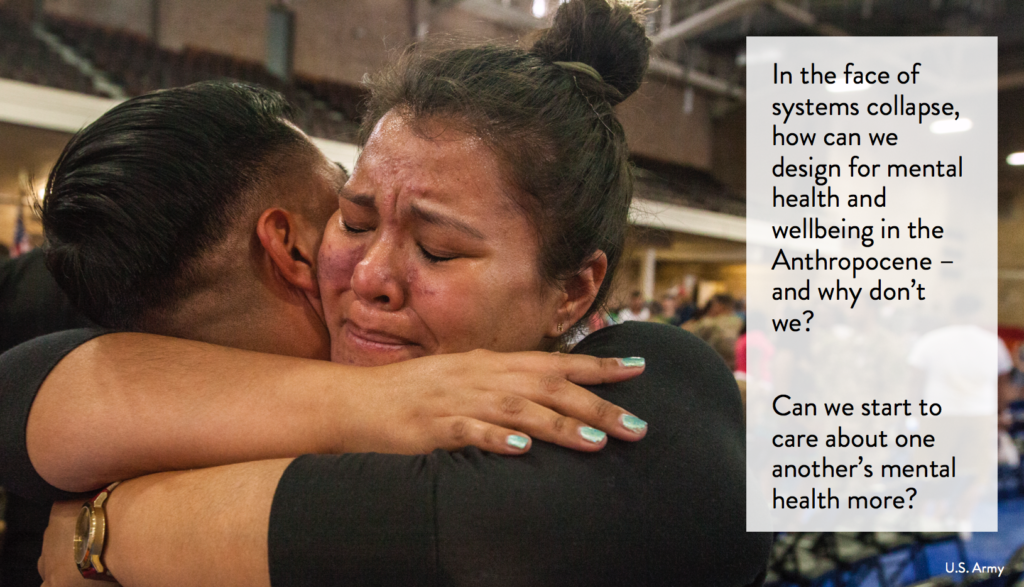

My thesis has been a four month project exploring these and other issues, culminating in an exploration to answer these questions And while this thesis is focused on those with a mental illness, this also opened up for me on a meta level emotion, illness and how vulnerable our societies are currently – and in the future – around mental health.

As we face massive issues like climate change, migration, economic stress, limited resources, we’ll need ways to help all people cope. How do we create resilience people to weather the massive changes ahead?

Every major issue we’ll face – issues like refugees, upheaval caused by climate change, the continued fraying of the social safety net and the middle class – mental illness can play a role in all of these.

The goal is to replace the negative infrastructure of stigma (and negative stories) about mental illness with a positive infrastructure of recovery oriented components with a goal to create a culture of participation to disempower stigma – and instead foster positive narratives via community.

We reject the need for darkness and outdated thinking about mental illness. We believe – without shame – in the remarkable ability of people to persevere, thrive and triumph, and especially through collective action. We move beyond state or market instead towards the collective expression of extrastatecrafts of peercare.

When we speak of wanting to change the conversation about mental illness, we speak of more than just improving healthcare treatment of mental illness – it means rethinking our relationship to illness, vulnerability, identity and individualism.

The conversation I seek to have is more than just based on ‘how might we…’ but rather is one where the language we use for the conversation erases the goal as being ‘to solve’ and instead uses design create conditions for exploration, activism, care and values that provoke meaning to rethink mental illness

What if our design interventions embraced peers helping each other outside of the need for medical authority? What if our work as designers challenged our concepts of illness and authority? What does it mean to do this work, and when can it start?