My research looked at medium (if an object, if held for support or an experience not dependent on touch) and usage (‘passive’ consumption or ‘active’ participation involving creativity, single or repeated use, if public or private and are ceremonies involved). I then categorized precedents into purpose, care, and knowledge sharing, knowing that categories overlap and interventions often took multiple forms. Precedents aren’t necessarily therapeutic for self-stigma – I included work in public stigma related initiatives if it was thought-provoking or could be extended in new ways towards self- stigma.

What interventions currently address stigma and self-stigma? What methods do they use to evoke connection, create engagement, provide support, and any other goals, and what mediums do they use and why? I found dozens of projects that in some way addressed stigma or self-stigma and explored different scales of intervention. I also looked on a deeper level of what the use of intervention meant – was a concrete object to be held for support, or an ephemeral experience to be experienced and not dependent on touch or any particular sense? Was there a focus on ‘passive’ consumption of something, or more ‘active’ use of the product where participation or use also involved creating and reflection on self-stigma as part of its use? Would it be used a single time or repeatedly, and were there ceremonies or infrastructure around the interventions? Were other people involved in the use, and if so, was it in public or private? With these questions in mind, I grouped my research into broad categories. The main characteristics for grouping into categories was the primary purpose, from awareness (raising awareness) to care (providing a service) to knowledge (sharing resources) – knowing that categories overlap and are not comprehensive. I also noted the medium –a person (peer to peer support), object/story, space, or a combination of mediums. Even within this, many objects took multiple forms, from objects to hold, to objects to be worn and categories. Precedents aren’t necessarily what would be used therapeutically for self-stigma – I included work in public stigma related initiatives if it was thought provoking or could be extended in new ways towards self-stigma. The ones that resonated with me the most for today include the following:

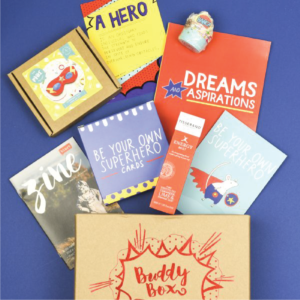

Buddy Box

UK • Objects of care • focus on care to provide a service

https://www.blurtitout.org/buddybox/

Buddy Box from Blurt It Out in the UK is a subscription box full of ‘thoughtful, mood-lifting treats’ that is a ‘hug in a box’ – that line alone is what drew me to this as an inspiration. (Even the concept of a ‘buddy in a box’ feels endearing) They have both a one-time purchase and a reoccurring purchase subscription service, and the objects vary month to month, usually in the notebooks and notecards and bath related products. It interestingly highlights a tension – while Blurt It Out, the organization running the service, describes itself as ‘increasing awareness and understanding of depression’, it also sees brands the Buddy Box service as something open to anyone. There is also a tension in that so much of the interventions in this space embrace a ‘touchy-feely’ branding in the selection of objects and visuals, something I’d like to escape if possible.

Key take away:

What would consciously including evocative objects of care as part of the experience of mental illness do to change the dynamic of how we view mental illness?

Painted Brain

spaces and activities • focus on community

Painted Brain ‘creates lasting community-based solutions to mental health challenges and the impact of social injustice through arts, advocacy, and enterprise’. A strong survivor, consumer and anti-psychiatry focused group, their activities center on group art and writing and has explore multiple mediums, including publications and community spaces, but as a non-profit they have struggled how to operationalize the service and how ‘exclusive’ they want to be – is this just for consumers, and if so, how do we grow a community where the number who self-identify may be limited because of stigma?

Key take away:

What would consciously creating an arts community around mental illness be like, and how do we sustain it if it is peer run?

Project Semicolon

Global • objects • focus on care

This project looks to ‘present hope and love to those who are struggling with depression, suicide, addiction, and self-injury’ and transform something highly charged and rarely spoken of into something worth understanding and empathizing with through the use of a common symbol tattooed onto self-identified participants in the community. It has since become a symbol of solidarity and a community for those who resonate with the symbolism of the object; as founder Amy Bleuel described it, “in literature, an author uses a semicolon to not end a sentence but to continue on – we see it as you are the author and your life is the sentence. You’re choosing to keep going.”[1] The evocative power of this symbol is something I want to capture, although the power of it has taken on a new sadness; at the time of writing; Amy has since committed suicide. Her death only serving to highlight the incredible struggle mental illness can be for so many, and the need to create more interventions to help.

Key take away:

What would consciously reframing the aesthetic of mental illness to involve celebration of perseverance do for a community?

Sanctus

UK • events • focus on care, education, support

The founders recently started this non-profit that seeks to ‘change the perception of mental health’ to be more ‘like physical health and we want to put the first mental health gym on the high street.[2]” They have community social events, training and educational outreach efforts to businesses, clothing and their goal – to normalize discussion of mental illness and focus on education for all on this topic – is inspiring, as is their efforts to have a variety of social events in public. Their branding is positive without feeling too New-Agey – a clear appeal to me.

Key take away:

what would consciously ‘rebranding’ mental health feel like, and what role are events in this work?

South West Yorkshire Mental Health Lab

UK • spaces and activities • Focus on services

http://reospartners.com/projects/south-west-yorkshire-mental-health-lab/

This lab was a one-time event where doctors, psychiatrists, district nurses, district managers, caregivers, and consumers all co-created prototypes of new kinds of services in response to needs in the community. It also recognized the power of a multiple stakeholder perspective, and explored different kinds of artifacts and spaces from multiple perspectives. It recognized that it’s not enough to want to create a community – what will they be doing when they come together, and can that respond to the needs of people in the future as a living service?

Key take away:

What would consciously creating living services around mental illness be like to respond to ongoing needs?

The Temple at Burning Man

Black Rock City, Nevada • spaces, activities, objects • focus on care and community

Burning Man is an annual week long arts festival that has run for over 31 years, and as a precedent is a complicated example to distill down to a paragraph. Though I have been 3 times, it’s difficult to describe an immersive experience that focuses on community in temporary autonomous zone that explores a community’s culture and the role of ritual within it. The Temple started in memorial to a Burner who died, and every year is created as a place for people to mourn and celebrate people in our lives who have died. People are encouraged to contribute to its building and evolution, and peers become counselors or ‘Guardians’ within it. It seeks to connect us to of the need of rituals and to use space, activities, objects and stories together as an experience to heal from grief, similar to Alexei Lidov’s concept of hierotopy, or ‘sacred space’ for collaborative emotion[3].

Key take away:

What would creating a space for the sacred and incorporating rituals mean for a design intervention around mental illness – and how do we do so in a secular, individualized time?

Take aways from this work – and opportunities

The popularity of multiple mediums as an established best practice

Many interventions used a multi-media approach. I started to map these out in a box model, but found that extremely difficulty since multiple components can live in multiple places, and a gap between two extremes (individual vs. group, private vs. public) does not necessarily reflect a missed opportunity but rather no need for an intervention. Mapping to a criteria was also challenging, as criteria can be extremely subjective. What did interest me was the idea of a design intervention using multiple mediums something I took forward into prototyping. Even if I wouldn’t be able to prototype all of the mediums – public space, in particular, is difficult to prototype within a limited budget – the ability to think of a transdisciplinary approach of multiple mediums working together inspired me, and to see this as something recognized by others was heartening.

The limits of public education and awareness – storytelling fatigue

Many interventions were great at starting a conversation to address public stigma using storytelling, which is important for acknowledging one’s journey to bear witness to trauma. At the same time, ongoing community support around an intervention could be problematic, and the act of simply telling a story and sharing one’s experience has limited usefulness for ongoing support for self-stigma. At a certain point, storytelling fatigue sets in. I also consciously looked for interventions that either acknowledge the limits of mediums or purpose, and looked to have some longevity. For example, the South West Yorkshire Mental Health Lab was a one-time event where doctors, psychiatrists, district nurses, district managers, caregivers, and consumers all cocreated new kinds of services in response; that it saw a need to co-create services rather than share stories is one thing to encourage, as is the idea of consciously looking at the needs and creating new rather than sticking to existing mediums (like storytelling).

The formation of criteria – what to start bringing into prototyping

I started identified key criteria as areas of exploration after looking at the interventions, which were another way to narrow down the scope of mediums I was interested in working in. Not all precedents could touch on all of the criteria, but these were starting to become clear as areas of exploration especially with the secondary research I was conducting at the same time. I feel uncomfortable coming up with a rubric for interventions (‘BuddyBox got a 3/10 for political, but really shines on that emotional criteria, so we’ll advance it to the next round’) and instead see each of these as signposts helping me pick which road forward I wanted to go for. The criteria include:

- emotional or evocative: the intervention aims for symbolism rather than direct representation and aims to be subtle and supportive rather than ‘harsh’ and prescriptive

- empowerment: the intervention aims to increase agency and action of its user – to make the benefits of action clear

- intimate or portable: the intervention should aim to operate on an intimate level, perhaps via portability or being used individually

- personalizable: the intervention should aim to be personalized to meet the needs of the user through options to customize the interface

- political: the intervention aims to incorporate activism or a political dimension on some level in the activities it offers if it is based on activities

- recovery oriented: the intervention should include or reflect recovery-based language that looks at the person holistically rather that as ‘just a patient’

- reflective: the intervention should aim to create a reflective mindset that challenges thinking in the use

- social: the intervention should aim to connection people in real life with events (both as a community of mental health consumers, but perhaps with the general public).

[1] McGlensey, Melissa. “The Powerful Reason People Are Putting Semicolons On Their Skin”. The Mighty. N.p., 2017. Web. 10 Apr. 2017.

[2] “Sanctus”. Sanctus. N.p., 2017. Web. 10 Apr. 2017.

[3] Lidov, Alexei. “Hierotopy: The creation of sacred spaces as a form of creativity and subject of cultural history.” The Creation of Sacred Spaces in Byzantium (2006): 32-57.