When we speak of mental illness in 2017, there is much we can say that points to progress, but also so much that needs improvement. We have evolved from a past of ‘madhouse’ psychiatric institutions with inhuman treatment, and have made inroads on the treatment of mental illness. Yet progress towards addressing stigma around mental illness has not been as successful. Mental illness itself is a world of different illnesses and treatment, and stigma, too is just as complicated, and they reveal some of the larger wicked problems within healthcare. At a larger level, mental illness and stigma speak to the difficulties of delivering care in a healthcare system under stress, and speaks to how we think about illness in general. Each domain of this points to its complexity as wicked problems.

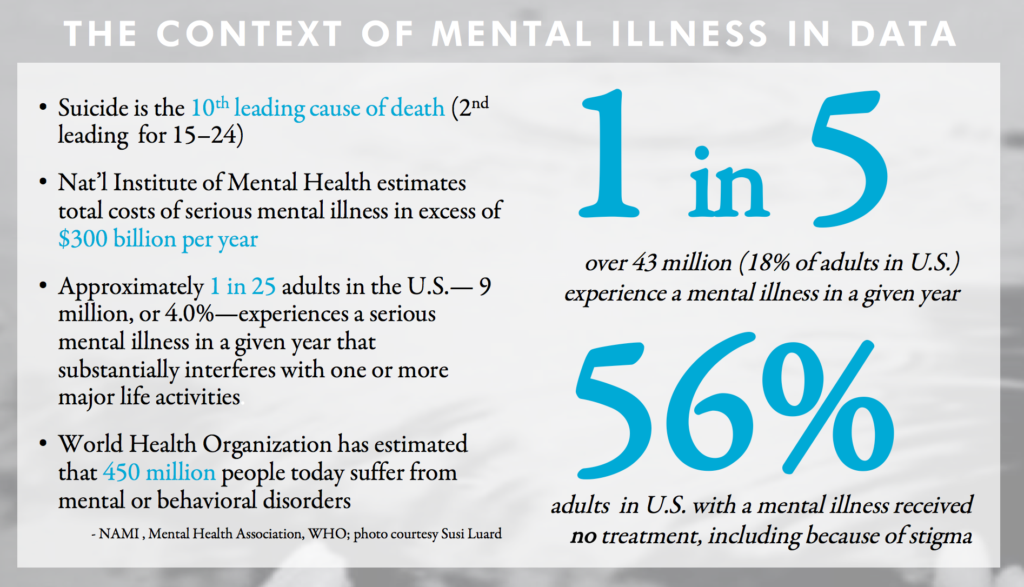

Mental illness is a complicated domain. While mental illness is persistent across the globe[1], in American 1 in 5 (43 million Americans adults, 18% of the population) have a diagnosable mental disorder that they have experienced within the past year [2]. On a systems level, many experience difficulty and do not receive treatment because of cost, a lack of medical professionals, issues in diagnosis, poor response to medication and more. In addition to these complexities lies a widespread stigma that often discourages those who would benefit from treatment from even seeking it[3]. Stigma, too, is as complicated as these illnesses. It exists across ‘the life cycle’ of illness – stigma and ignorance about medication and treatments, daily life, long-term prognosis– and a lingering undercurrent of fear about a link between violence and mental illness, that angry mentally ill people could ‘snap’ at any time. We also have multiple examples of how stigma is experienced – how people view and act towards those who have a mental illness, but also self-stigmatization when those with a mental illness internalize the stigma. Mental illness is for many an invisible disability, a backpack they wear that weighs one down but can never be revealed or removed – to reveal its presence risks encountering the stigma and being labeled or ‘outed’ as being mentally ill. The presence of stigma itself is a demonstration of human relationships of social groups and how we view each other and our differences, so often reflected in our culture(s) and media. Stigma is a function of ‘othering’; as Frederic Jameson writes, “a culture is the ensemble of stigmata one group bears in the eyes of the other group (and vice versa)”[4], and stigma becomes a mirror to understand human relationships and how we view and treat ‘The Others’ among us.[5] And while we are conscious of many identifiable groups who experience inequality, we still may not even see those with mental illness as a group or those to be helped – that somehow they’re not ‘really disabled’ because they are not physically disabled, revealing a hierarchy even among disabilities. Social movements around civil rights for gender equality, LGBTQ and racism have made great progress in changing perceptions, institutionalizing equality and addressing stigma against these groups. Yet stigma against those with mental illness persist, and has not decreased despite public education efforts, public figures disclosing they have a mental illness and improvements in how we diagnose and treat. The challenge of illness as a formation of identity is complicated – if we want to create social change, we require identity politics and the willingness to identify one’s status of having a mental illness, but if we have stigma we often fail self-identify, and wonder why nobody challenges that stigma, and fail to take responsibility in keeping that stigma in place.

The cost of stigma to us individually is also a massive cost to society as a collective. The costs of mental illness – and the role of stigma with it – for untreated mental illnesses in the U.S. is more than $100 billion a year in lost productivity[6]; if we are to look at both direct costs (direct expenditures for mental health services and treatment) and indirect costs (expenditures and losses related to disability, include public expenditures for disability support and lost earnings), The National Institute of Mental Health conservatively estimates the total costs associated with serious mental illness to be in excess of $300 billion per year[7], and the cost of coping with these and other complex chronic medical conditions is daunting. When we expand outward to consider the role mental illness plays in social issues of substance abuse, homelessness, LGBTQ youth, veterans and those experiencing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, the urgency of the crisis of mental illness becomes even more pronounced – and also highlights the difficulty of addressing these often overlapping complex adaptive social issues.

The work highlights tensions about some of the core concepts that shape our understanding of society – agency and authority (who leads care – the physician, the patient or others), engagement, and identity. Additionally, the context of delivering healthcare among these tensions will continue to become more complicated as it shifts towards a System Medicine approach based on the ‘P4’ model of medicine (predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory)[8] Will we be able to make such shifts with gaps in treatment? The gaps in the space of stigma and self-stigma are numerous. Access to mental health resources that can address self-stigma is an issue – things that may ‘work’ (such as psychiatrist-lead therapy) aren’t accessible to all, and even where peer to peer support exists, uneven implementation in the face of financial pressures creates gaps in access to such services. Compliance support is another gap – personalized recovery plans exist, but knowledge sharing is uneven and seen as ‘individual’ activity, reinforcing the dogma that success as an individual is tied solely to effort alone and not community. There are also issues with recovery not carrying over after hospitalization for many. There is often a lack of a multi-modal approach even among those with resources – those who can afford therapy do not engaged in larger meta narratives of action to fight stigma. Stigma is seen as someone else’s problem, and few linkages between healing, activism and ongoing connection to community exist in a highly individualized country like the U.S.

Self-stigma lives in every day experiences at a systems level when experienced through discrimination by many with a mental illness (i.e. unemployment, being fired due to illness, the financial cost of treatment), but also silently in day to day moments when those with a mental illness are alone, without support structures. We know that stigma prevents people from getting treatment, and we also know public education campaigns like the City of New York’s ThriveNYC are working to get more people into treatment and to create more treatment options. Yet little is done to address self-stigma, and usually not from the perspective of design – cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and online stories discussing self-stigma are effective to some degree, but both depend on patients either knowing they exist, having access to them, or proactively seeking those options. If we seek to understand moments when people experience self-stigma, can design help alleviate those moments of extreme emotional distress? Perhaps at a deeper level, my ‘why’ in the project is also to ask why design should stay away from helping those with self-stigma, when design can create interventions of comfort and care, ways to reframe realities and new alternative systems. It’s a recognition that while medical treatment and the medical model of illness is core to successfully living with the biological part of mental illness, a recovery oriented approach is an area, too, to address the social part of living with mental illness, and an opportunity where design can play a role. As the U.S. moves towards more ‘collaborative care’ models of healthcare, patients-as-self-advocates proactive in their care, Community Health Centers and peer to peer support all become key to help an overburdened healthcare system. Yet peer to peer support isn’t stressed in the treatment plans created for and communicated to patients in the mental healthcare systems – a level of proactive hunting for information about psychiatric support is usually done by patients. The Internet has made sharing information about treatment far easier, but gaps still remain in making peer to peer support and self-care effective and accessible for all. Online peer to peer support sites and storytelling about stigma and mental illness both exist, but those assume all have access to those resources. Even where there are methods to get people online – like libraries with free computer terminals – operational system challenges exist. The Brooklyn Library limits access to free terminals to half hour sessions, often with no privacy, so someone many not feel like accessing resources about mental health on a public terminal which others can view. A perceived ‘solution’ – online stories about mental illness – can sometimes not fit the accessibility needs of the audiences that would benefit from them the most.

The wicked problems of mental illness and self-stigma require both systems thinking to address gaps in care, but also humane solutions focused on both medicine and recovery – and a transdisciplinary design approach is able to address the system and the humane solution. Is there a way to create design interventions that builds on the ‘contact’ part of stigma reduction which we know is successful by leveraging peer to peer support? Can we be more holistic and proactive in addressing self-stigma as part of treatment, and work to integrate the medical model with the social model of illness together through proactively informing patients about peer support to become truly patient centric? What can be done to help detangle the mess of care for mental illness and change the narratives of stigma that keep it in check?

Beyond economics, the importance of understanding mental illness and stigma is valuable in understanding how complex adaptive systems often operate in ways that are invisible to us. We prioritize fixing systems that have failing physical infrastructures – the bridges that threaten to collapse in front of us – because they are physically present, and they have value to us as part of a commons. Designers are so adept at understanding touchpoints and designing better artifacts within systems, and addressing those visible infrastructures. Invisible infrastructures – including data, policies, language, how knowledge is structured, and social behaviors – are still so often “shared standards and ideas that control everything [as a] the point of contact and access between us all […] the rules governing the space of everyday life[9].

They are invisible infrastructures which are harder to grapple with – and often what designers have avoided. Stigma can be seen as an invisible cultural infrastructure, a lens to understand human behavior and the values that drive that behavior, and to understand how groups view and enforce cohesion. Its presence can tell us if social progress has occurred, incredibly important since stigma can affect one’s willingness to ask for help in treating a mental illness. Stigma and shame also can be mirrors to how groups enforce their behaviors and norms – how stigma becomes a “cultural practice[s] [and] ways that public shaming practices enforce conformity and group coherence”[10]. Stigma and shame highlight the use of silence and avoidance as levers in a system of control, which keep the cycle of stigma perpetuating. Like an Ourobos – the snake that eats its own tail – the cycle of shame and stigma keeps the system of ignorance against those who have a mental illness flourishing. We see how this operates as few publically identify with having one – it is a club that nobody wants membership to, let alone pride in membership – out of fear of reprisals from disclosing[11]. We don’t have a language or a way to talk about mental illness or associated stigma – often only in hushed tones, or at a point of crisis when drastic medical intervention is required. This is the invisible infrastructure and systems of power at work – one does not talk about one’s hospitalizations, for example, except in close company, and even then, perhaps not. There is also a lack of public dialogue and public spaces to discuss anything to do with mental illness; while support groups exist, they are geared towards those with mental illness (or their family members) and not towards dialogue with those who do not have mental illness. We may rush to a town square (virtual or actual) when a devastating global news event occurs or a public figure dies to lay our flowers or candles – but when many are hurting every day, we seem unaware of how to even feel or talk about the issue. There is also the complication of transient states of identity and membership – one may not consistently live with mental illness, those who do have one may not see it as a form of self-identity and even if they do, they may not wish to publicly reveal its presence or membership. At its heart, mental illness is tied to our perceptions and value about agency, willpower, self-control and failure, and stigma against those with mental illness often reveal our own fears about it.

That fear, in a sad kind of irony, is a universal condition, a unifier among all our disparities. And stigma and fear, their very presence raise a solemn question – how do we use design to raise visibility of invisible disabilities, when the stigma itself discourages the act making visible? Can we create new kinds of biopolitical[12] infrastructure(s) to fight stigma – to ‘kick at the darkness till it bleeds daylight’?

The wicked problem of mental illness

We see that mental illnesses is a wicked problem analyzed through lenses of psychology and politics in particular. Around the concept of psychological problems and possibilities, we can see while that mental illnesses are largely treatable, treatment itself is a complicated consideration. There are multiple models of treatment, just as there are many mental illnesses, and complexity of treatment is due to the personal nature of illness – everyone’s needs are different. Medication is one common ingredient of a treatment plan, but there are issues of medication adherence, cost, side effects and perceived need to not use medication – and that for some, medication fails to work. The concept of medication itself brings up a key issue – a certain level of tension lies at the heart of healthcare treatment around how we view and treat illness. There is a more illness based view (the ‘medical model’) that focus on illness as a biological issue to eradicate, but there is also a recovery-based view (‘social model’) that also focuses on recovery and resilience on living with a chronic illness, a juxtaposition with its roots in the Disability Rights movement. The first line of defense in treatment of mental illness in the medical model of illness is psychopharmacology (the management of psychiatric medication) and therapy. This lies in contrast to a recovery based view of illness focusing on building up skills and resilience. This isn’t necessary a clear ‘either/no’ dichotomy, and there is overlap – for example, when a social worker employed in a psychiatric facility works to provide social services within an institution which is based on a medical model – but it does raise interesting systemic views of authority in systems – the use of peer to peer support may be seen as disruptive by some in the medical profession, although their presence as ‘distributed support nodes’ creates a kind of ‘back up’ system for the mainstream medical system.[1]

And when we speak of psychology, we speak of recognition of the self, too – and the concept of identity as it relates to illness. The complexity of identity and mental health means that those with a mental illness may not identify as being mentally ill or consider ‘mental illness’ as an important part of their identity – and even if they did, they may feel stigma disclosing it publically. Mental illness is for many an invisible disability, a backpack they wear that weighs one down but can never be revealed or removed – to reveal its presence risks encountering the stigma and being labeled or ‘outed’ as being mentally ill. This can also be a transient identity – some may have a mental illness once, and never again. Even among serious mental illnesses (SMI) like schizophrenia which are chronic and multi-year in duration, there can be a huge variation on how an illness affects a person over their life. Identity is yet another lens to understand illness and possible problems and possibilities.

Looking at political problems and possibilities, there is often a lack of treatment for mental illnesses due to stigma and difficulties in accessing care because of a lack of resources (trained medical professionals), issues of diagnosis (and misdiagnosis, since some diseases share overlapping symptoms), poor response to medication – and of course financial constraints, now only exacerbated by a lack of health insurance with the repeal of the Affordable Care Act and the possible return of discrimination against those with mental illness by an inability to get coverage because of a pre-existing health condition:

Even among those who have health insurance, psychiatrist often don’t take the insurance, or partially cover it. Laura Pogliano of Towson, Md. has often paid out-of-pocket for the care of 22-year-old son, who has schizophrenia. He frequently has needed care that wasn’t covered by insurance. Other times, he couldn’t wait for a public hospital bed to open up. In less than three years, Pogliano says, she exhausted all $250,000 of her life savings. She lost her house when she chose to pay his hospital bills instead of her mortgage payments. “Every parent I know,” she says, “has to fight for treatment for their child.”[2]

Gaps in existing treatment occur as our healthcare systems struggle to provide service in a patch-work mega system that is often underfunded or under staffed[3]: The idea of systemic challenges in the financing of healthcare lead to discussions of scalability of providing services and even how we measure success. When we speak of treatment, we are speaking about effectiveness of something that can be measured, but this can pose a challenge for designers working in healthcare. Design often has different metrics of success – how should design measure the success metrics of a design intervention when the standards of success for medicine is often different (i.e. randomized trial in a peer reviewed journal etc.) – as Corrigan so aptly notes, “different research paradigms make different assumptions and claims about validity”[4]. While a move towards patient satisfaction is occurring as a recognized benchmark in delivering care, the tension between quantitative metrics of success (shorter wait times for care, shorter duration of illness etc.) and qualitative metrics of success (improved quality of life, reduction of self-stigma) still lies as a concern within health care – if both are to be measured, held equally or something more.

How we understand mental illness becomes even more complicated when we understand how it plays a contributing factor mental illness plays some of our most complex challenges, including other illnesses and issues of social justice – the social problems and possibilities. Mental illness often has a relationship to alcoholism and substance abuse (as a method of self-medication) and is often present with other diseases, including complex chronic diseases (such as diabetes) and terminal illness. Even individual conditions like depression occur in conjunction with other psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety (‘comorbidity’). And mental illness is intertwined with some of the most complicated human services challenges in social justice (and criminal justice) for marginalized communities, including the homelessness, those who have experience in the justice system, LGBTQ youths, poverty and Veterans. The issue of treatment for the marginalized, too, is complicated. These two lenses – disease and social justice – help add weight to the claim that mental illness is a wicked problem operating with and within many complex adaptive systems. There’s also evidence that social anxiety and loneliness are on the rise[5], adding to the urgency of the issues. This sense of mental illness being a ‘contributing factor’ to other social issues complicates capturing data. We know rates of suicide and mental illness among LGBTQ youth, for example, is high – but it’s uncertain how to aggregate ‘up’ this data to our understanding of mental illness, stigma and treatment.

The wicked problem of stigma about mental illness

If the landscape of mental illness is complicated, so too is stigma. We understand that stigma is prevalent still in 2016:

Research suggests the country has made fitful progress in fighting stigma. Large national surveys conducted in 1996 and 2006 found that Americans increasingly understand mental illness to be a biological condition, rather than a moral failing. And the study found Americans have become more accepting of people with depression. Over the same period, however, Americans grew less willing over time to befriend or work with someone with schizophrenia, and more inclined to see people with the disease as violent and dangerous. Researchers have not conducted more recent surveys.[6]

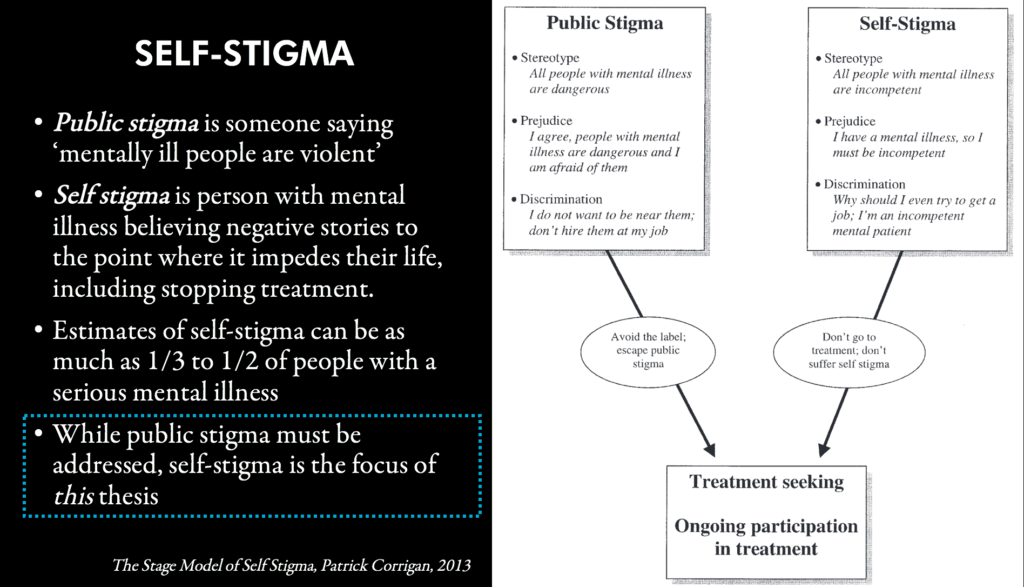

Public stigma and self-stigma (when someone internalizes negative stories) are intertwined and public stigma (in media and popular culture but also general attitudes) can reinforce self-stigma. Stigma can even differ depending on the mental illness[7] – stigma against those with schizophrenia is more prevalent than against anxiety disorders because of perceived link between schizophrenia and violence; at the same time, we also see a hierarchy that some illnesses (such as anxiety) aren’t seen as ‘true’ illnesses, something those in the neurodiversity movement (centered on advocacy around autism) are fighting. Even within the disability rights movement, some with physical disabilities may be viewed as in need of more ‘stigma reduction’ than those with mental illness or ‘invisible disabilities’. Complicating this is that multiple disciplines study stigma – social psychology but also ‘medical anthropology’, a subfield within social anthropology that looks to study cultural discrimination within medical treatment. This becomes the parable of the beggars and the elephant – each touching a different part of the elephant, each with their own perspective of what they find.

Mental illness is complicated – and so, too, is stigma. Mental illness and its treatment is a complicated wicked problem, and stigma, too, is just as complicated to address. While mental illness is persistent across the globe, in American 1 in 5 (43 million Americans adults, 18% of the population) have a diagnosable mental disorder that they have experienced within the past year. The costs of mental illness – and the role of stigma with it – for untreated mental illnesses in the U.S. is more than $100 billion a year in lost productivity; if we are to look at both direct costs (direct expenditures for mental health services and treatment) and indirect costs (expenditures and losses related to disability, include public expenditures for disability support and lost earnings), The National Institute of Mental Health conservatively estimates the total costs associated with serious mental illness to be in excess of $300 billion per year, and the cost of coping with these and other complex chronic medical conditions is daunting.

Social movements around civil rights for gender equality, LGBTQ and racism have made great progress in changing perceptions, institutionalizing equality and addressing stigma against these groups. Yet stigma against those with mental illness persist, and has not decreased despite public education efforts, public figures disclosing they have a mental illness and improvements in how we diagnose and treat. The cost of stigma to us individually is also a massive cost to society as a collective.

Stigma, too, is as complicated as these illnesses. It exists across ‘the life cycle’ of illness – stigma and ignorance about medication and treatments, daily life, long-term prognosis– and a lingering undercurrent of fear about a link between violence and mental illness, that angry mentally ill people could ‘snap’ at any time and become violent. Patients can even find themselves battling stigma from the very people there to help them, mental health professionals, who often too battle stigma for their work.

Beyond economics, the importance of understanding mental illness and stigma is valuable in understanding how complex adaptive systems often operate in ways that are invisible to us. We prioritize fixing systems that have failing physical infrastructures – the bridges that threaten to collapse in front of us – because they are physically present, and they have value to us as part of a commons. Designers are so adept at understanding touchpoints and designing better artifacts within systems, and addressing those visible infrastructures. Invisible infrastructures – including data, policies, language, how knowledge is structured, and social behaviors – are still so often “shared standards and ideas that control everything [as a] the point of contact and access between us all […] the rules governing the space of every day life. They are invisible infrastructures which are harder to grapple with – and often what designers have avoided. Stigma can be seen as an invisible cultural infrastructure, a lens to understand human behavior and the values that drive that behavior, and to understand how groups view and enforce cohesion. Its presence can tell us if social progress has occurred, incredibly important since stigma can affect one’s willingness to ask for help in treating a mental illness. Stigma and shame also can be mirrors to how groups enforce their behaviors and norms – how stigma becomes a “cultural practice[s] [and] ways that public shaming practices enforce conformity and group coherence”. Stigma and shame highlight the use of silence and avoidance as levers in a system of control, which keep the cycle of stigma perpetuating. Like an Ouroboros – the snake that eats its own tail – the cycle of shame and stigma keeps the system of ignorance against those who have a mental illness flourishing. We see how this operates as few publically identify with having one – it is a club that nobody wants membership to, let alone pride in membership – out of fear of reprisals from disclosing. We don’t have a language or a way to talk about mental illness or associated stigma – often only in hushed tones, or at a point of crisis when drastic medical intervention is required. This is the invisible infrastructure and systems of power at work – one does not talk about one’s hospitalizations, for example, except in close company, and even then, perhaps not. There is also a lack of public dialogue and public spaces to discuss anything to do with mental illness; while support groups exist, they are geared towards those with mental illness (or their family members) and not towards dialogue with those who do not have mental illness. We may rush to a town square (virtual or actual) when a devastating global news event occurs or a public figure dies to lay our flowers or candles – but when many are hurting every day, we seem unaware of how to even feel or talk about the issue. There is also the complication of transient states of identity and membership – one may not consistently live with mental illness, those who do have one may not see it as a form of self-identity and even if they do, they may not wish to publicly reveal its presence or membership. At its heart, mental illness is tied to our perceptions and value about agency, willpower, self-control and failure, and stigma against those with mental illness often reveal our own fears about it. That fear, in a sad kind of irony, is a universal condition, a unifier among all our disparities. And stigma and fear, their very presence raise a solemn question – how do we use design to raise visibility of invisible disabilities, when the stigma itself discourages the act making visible? Can we create new kinds of biopolitical infrastructure(s) to fight stigma – to ‘kick at the darkness till it bleeds daylight’?

The presence of stigma itself is a demonstration of human relationships of social groups and how we view each other and our differences, so often reflected in our culture(s) and media. Stigma is a function of ‘othering’; as Frederic Jameson writes, “a culture is the ensemble of stigmata one group bears in the eyes of the other group (and vice versa)”, and stigma becomes a mirror to understand human relationships and how we view and treat ‘The Others’ among us. And while we are conscious of many identifiable groups who experience inequality, we still may not even see those with mental illness as a group or those to be helped – that somehow they’re not ‘really disabled’ because they are not physically disabled, revealing a hierarchy even among disabilities. Even among those with identify as being mentally ill, that is a transient state, as illness itself can change and even among serious mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, patients can be stable with treatment for long durations.

Stigma is supported by a cultural infrastructure of fear, avoidance, silence and ignorance that keep stigma unchallenged and in place. The power of stigma is enforced invisibly through its silence – and media portrayals in popular culture of mental illness promote and reinforce negative stories of the mentally ill as being ‘mad’, ‘bad’ or ‘sad’. The stigma can lead to stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination and ‘othering’ – the creation of an ‘Other’ who is different and seen to be inferior because of their illness, and that their illness defines the essence of who they are. This in turn prevents many from even accessing treatment. This Othering is a social categorization, and invisible social practices are a kind of ‘invisible infrastructure’ keeps the stigma against those with mental illness in place – a scaffolding that leads to the building of laws, objects and spaces that further keep stigma in place. The lived experiences of those with mental illness is then one often of discrimination and marginalization.

Some may argue that in the face of massive changes in the healthcare system, a focus on stigma may seem less of a priority. But stigma and fear of those with a mental illness can have wide reaching effects in many aspects of a person’s life and future prospects – Corrigan highlighted four ways that the public may react to individuals with mental illness as a result of stigma:

- Withholding help: choosing not to assist people with mental health concerns because they are believed to be responsible for their condition.

- Avoidance: refusing to employ, rent to, or provide other services to people with mental health concerns.

- Segregation: moving people away from their community into institutions where they can be better treated or controlled.

- Coercion: mandating treatment or criminal justice responses based on the belief that people with mental illness are not able to make competent decisions.[8]

This can also include people avoiding seeking treatment, thus exacerbating the severity and duration of an illness which can lead to poor self-esteem and other conditions. And the cost of not getting treatment can be devastating – including the risk of suicide from an untreated mental illness.

Addressing stigma is a complicated challenge. Patrick W. Corrigan, a leading researcher on stigma, has conducted a meta-analysis of the work being done to study effective approaches to understand and eradicate stigma. He and his coauthors have categorized efforts into three categories: education, contact (with those with mental illness), and protest. Most of the focus of initiatives in the U.S. has been on public education – awareness campaigns. Yet Corrigan notes that the most effective method of eradicating stigma for adults in particular is through person, face to face contact interaction:

Although contact and education both seem to significantly improve attitudes and behavioral intentions to- ward people with mental illness, contact seems to yield significantly better change, at least among adults. This is especially evident in studies that used more rigorous research designs, such as randomized controlled trials. Mean effect sizes for contact when assessing overall effects as well as effects on attitudes and behavioral intentions were significantly greater than those found for education. Meeting people with serious mental illness seems to do more to challenge stigma than educationally contrasting myths versus facts of mental illness. (Corrigan 3)

Stigma can prevent patients from getting treatment in the first place, and self-stigma can affect their treatment as patient refuse to see the usefulness of taking medication and doing self-care activities if they have internalized a message of ‘why bother – I’m not worth it’. It’s important to note the sense of isolation experienced by many with a mental illness –even if they are in therapy, receive medication and have support structures, self-stigma can creep into their daily lives, and integrating CBT into daily life becomes a case of willpower – the patient has to constantly reframe negative thinking. If design is also about reframing, could we use design to help patients with that reframing through materialization of the benefits of a recovery oriented model?